The State Library of Victoria’s first librarian was, by any account, useless. “Marcus Clarke was a totally hopeless librarian,” admits historian Tony Moore. “When he was in with a hangover, he’d place a cigar in the mouth of the lions out the front so his mates knew to come up and see him.”

But it wasn’t for his middling bureaucratic skills Clarke was appointed to the fledgling institution. Rather, it was his reputation as a Melbourne Bohemian High Priest that got him the job. Emigrating from Britain at the age of 16, Clarke claimed to have been a member of the bohemian movement in Paris and London (“A bit of an exaggeration perhaps,” shrugs Moore). But, in a canny if counter-intuitive move, the library’s patron, Sir Redmond Barry, appointed Clarke to mix things up. “He was hired by Redmond Barry as a public intellectual and a stirrer,” says Moore. “He wanted to use the collection to start to talk about ideas and put the library on the map.”

Clarke used his very public position to advocate for a circle of talented writers, artists and journalists, founding a counter-cultural tradition that lives on in the city even today. So it’s fitting that a celebration of Melbourne’s fringe-dwellers should be held in the building where Clarke (nominally) worked.

We think you might like Access. For $12 a month, join our membership program to stay in the know.

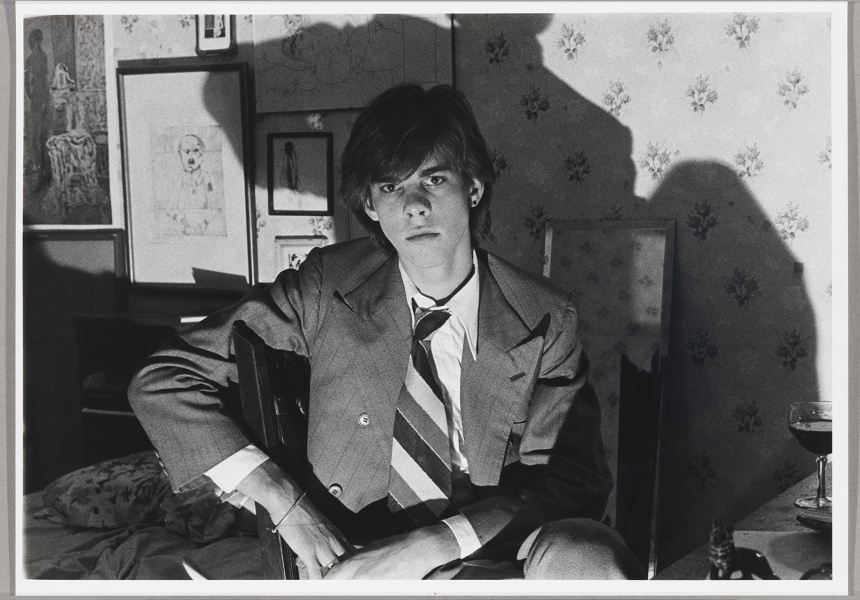

SIGN UPEntitled Bohemian Melbourne, the show collects hundreds of photographs, costumes, artworks, diaries, records and videos on the city’s sub-cultural history. Curator Clare Williamson, who has been working on the exhibition for two years, believes it’s important to remember that the significant avant-garde movement wasn’t purely a European phenomenon. “When we look back on bohemian culture, we often think of overseas examples like the Beat poets or the Haight-Ashbury,” she says. “I think people here might not be as conscious of the rich local heritage that there is going back 150 years.”

Bohemians first appeared in 19th-century Paris, their name referring to the gypsy culture from which they drew influence. Moore believes the lifestyle’s inception coincided with the beginnings of modern capitalism; increased urbanisation and the beginnings of an art market encouraged creative types to not only professionalise their practice, but to push back against “mainstream” society. “It was partly as a response to the commercial production of art, but also the anonymity of the modern city,” explains Moore, who studied the sub-culture in his book Dancing with Empty Pockets. “The life of an artist is never an easy one, so there’s a constant need for a kind of push-back. Bohemianism is as much a more interesting version of a trade union. It says, ‘Here I am, I’m as important as a coal miner, a mechanic’.”

In Melbourne, high immigration and a globally connected populace made the city fertile ground for the subculture. “It’s about Melbourne growing from a tent town to a great metropolis of the empire,” says Moore. “There was a very large educated middle class in 18th-century Melbourne. Places like Australia and New Zealand have always been connected to the media, and the circulation of radical ideas is part of that.”

Along with writers and journalists such as Clarke, artists from the Heidelberg School, such as Tom Roberts, held conversations at his studio in the Grosvenor Building, while the Lindsay brothers staged mock Masonic rituals in the seedy Little Lonsdale area. “A lot of bohemians used to like to brothel creep,” says Moore.

The tradition continued well into the 20th century with groups such artists Albert Tucker and Sidney Nolan’s Angry Penguins, performers Vali Myers and Barry Humphries and the avant-garde theatre scene that coalesced around La Mama in the ‘70s – whether they called themselves “bohemian” or not. “Every generation sees themselves as the bohemian, then they see the ones behind them as not the true bohemians,” says Williamson. “I think that word, ‘bohemian’, might have found favour again. In recent years that word has returned, with boho fashion and bohemian balls.”

According to Moore, bohemian culture continues to flourish in Melbourne because the Victorian community values its artists in a way other cities don’t – although he admits we’re often late to appreciate them. “Culture is an asset of Melbourne that’s treasured by the people. Melbourne welcomes the iconoclasts later in their careers, and then treasures them,” he says. “Artists care about the nation and the public good in Victoria, and Victoria cares about artists. In Sydney, artists have to care about artists because no one else will.”

The paradox in the fact that a major state institution is lauding the work of artists who consciously struggled to stay outside the system is not lost, however. “I know there’s a certain irony in bringing together a group of people under any sort of label like that,” says Williamson. “In contemporary society, there’s not really any mainstream you can work against. Maybe it’s harder because it’s more diverse. There’s certainly no one single bohemia now.”

Bohemian Melbourne runs at the State Library of Victoria from Friday December 12, 2014 to Sunday February 22, 2015. Tony Moore will be hosting a series of walking tours taking in the lost sites of Melbourne’s bohemian history. For more details visit slv.vic.gov.au/bohemian-melbourne

Broadsheet is a Bohemian Melbourne media partner.